“Prayer to Aphrodite”

On your dazzling throne, Aphrodite,

sly eternal daughter of Zeus,

I beg you: do not crush me

with grief

but come to me now — as once

you heard my far cry, and yielded,

slipping from your

father’s house

to yoke the birds to your gold

chariot, and came. Handsome sparrows

brought you swiftly to

the dark earth,

their wings whipping the middle sky.

Happy with deathless lips, you smiled:

“What is wrong, Sappho, why have

you called me?

What does your made heart desire?

Whom shall I make love you,

who is turning her back

on you?

Let her run away, soon she’ll chase you;

refuse your gifts, soon she’ll give them.

She will love you, though

unwillingly.”

Then come to me now and free me

from fearful agony. Labor

for my mad heart, and be

my ally.

Greek Lyric Poetry

(Tranlated by Willis Barnstone)

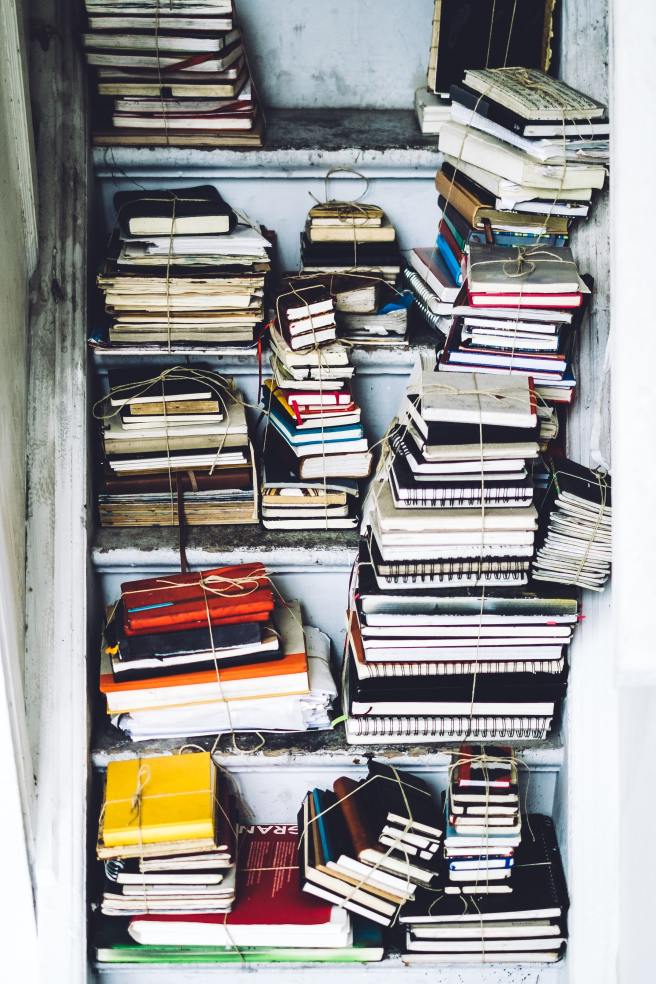

I often wonder: if governments and churches have their way, and our lovely planet is destroyed once and for all; if every human was destroyed, except for maybe two who could read and probably voted for Hillary Clinton; if all that was left was a pile of rubble, stacks of stones upon which were inscribed curiously translatable fragments of our letters and poems: what would those two readers think? What would they make of our thoughts, fragmented in piles? Would they find them beautiful, meaningful, intelligent, perhaps feeling? Or would our words betray the smallness of the age and its people?

Sappho is fragmented. The woman who was once famously described by Plato as the 10th Muse, whose works were, as far as I’ve learned, considered required material for those who wished to consider themselves educated — she was fragmented. Somewhere in the eleventh century, she was destroyed by a church seemingly at the height of its power. The faithful were promised indulgences for destroying Sappho’s words, get-out-of-hell-free tickets for those courageous enough to burn them.

It evidently worked. The poem copied above is, to my knowledge, one of her few surviving works, most of which are extant only because they were copied by scholars in lands the church had little control over. I wonder, still, what was lost — and wonder if my namesake, Pope Gregory VIII, mightn’t be one of the clerics Dante would later condemn to hell in The Divine Comedy. In my humble opinion, he should be.

But like so many beautiful voices, the fragments still testify. They speak — of beauty, love, lust, human desire. They speak in a way that brings me to my better self. Over years and years of teaching, I would pass out this poem with other fragments and ask students: why do you think Sappho was burned? Classic answers work, and are probably effective. There’s the feminist angle, and it is powerful: the Church’s actions are yet another example of silencing women. There’s also the sexual issue (students really tended to center here): Sappho was from Lesbos, and seems to have a rather fluid notion of sexual attraction; therefore, the Church sought the destruction of anything that might lead readers into what was once called “the unconscionable perversion of the Greeks.”

True. Solid. And real. Nothing to discount here. But I’ve been thinking that there might have been another reason for her burning. Sappho was into women, and men, and sex in general; she was honored even though she did not have the genitals required for honor in, well, nearly every culture. But underneath these rational reasons to account for the destruction, I’ve come to think there might be another, more irrational, shadowy explanation of the church’s action: it was terrified by Sappho’s relationship to the divine. To spirit. To inspiration itself.

We’ve been taught to live on our knees. To honor the gods as above us. We imagine divinity as somehow parental, a relationship in which a child is subordinate to those who came before. We exist as an act of grace, and as such have no right to expect anything. Inspiration in this model doesn’t come to us when we call; it comes to us when it chooses, when we need instruction, when deemed necessary for our edification.

That’s not Sappho. Sappho’s relationship with Aphrodite is not as child to parent (though the goddess is honored with golden description). If anything, Sappho is more like a sister to Aphrodite — and perhaps even more than a sister. Notice it is the goddess who comes to Sappho, who leaves her house when Sappho calls. She doesn’t have to; she wants to. She becomes, effectively, Sappho’s servant — her loving, caring servant, asking her what she wants. Wow.

And then she goes further: she says, look, I’ll do this for you…but it won’t produce what you want. AND THEN LEAVES THE DECISION TO SAPPHO! Wow! No pat on the head, no refusal “in the interest of good judgement,” but instead “I trust you.”

A god who trusts us. A Muse who rushes when we call. Who lets us be the guide. And, probably importantly, doesn’t need to work through institutions (that have a penchant towards destruction). Sappho imagines — or knows — god as personal. Giving. Trusting. A servant-god. That vision is what the Church tried to destroy.

Makes you wonder what they replaced it with.

Oh, yeah. We don’t have to imagine. But, if I may, we do have to remember.